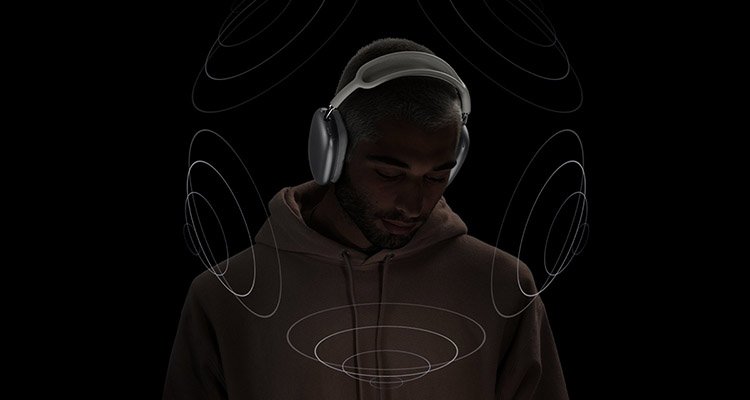

Photo Credit: Apple

Back in May, Apple announced a partnership with Dolby to deliver Spatial Music to all Apple Music subscribers. Keenly paired with Apple’s Airpods line of headphones, this is immersive audio’s most significant move to the mainstream.

As an advocate of the creative opportunity spatial music affords, the announcement was very exciting to me. However, since the launch of the upgrade this summer, some curious listeners and audio engineers wonder why the Apple version of Atmos sounds different.

Those listening closely have noticed that their favorite songs sound different, and not just because of the obvious remix in surround sound. It seems that Apple’s flavor of Dolby Atmos sounds quite different from what is heard in the studio. At the risk of sounding reductive, Atmos+Apple Music sounds bad.

Recently, a friend forwarded an insightful article that Edgar Rothermitch published on Pro Tools Expert. As an audio engineer myself, the article sheds light on why my music sounds so different when I listen to it on the iPhone. For months, I’ve been doing tests, asking colleagues, researching, and even asking people at Dolby what’s going on. However, no clear answers seem to exist.

As the Rothermitch article points out, Apple and Dolby offer a multi-step, convoluted process for an audio engineer to preview what their mix will sound like on Apple Music.

For some strange reason, this mix sounds quite different from what the mixer listens to in the studio through the professional Dolby Atmos Renderer (DAR) software. DAR is what software engineers use to monitor and “package” music into the master ADM format that Dolby uses for Atmos. Listening through DAR is nicely transparent with pretty easily expected results. But as the article lays out, by the time this ADM file gets converted for preview on the iPhone, the mix sounds quite different.

The technical reasons why the mixes sound different turns out to be a combination of Apple’s decision to use its own Apple Spatial Audio Renderer with a consumer delivery format of Dolby’s called Dolby Digital Plus Joint Object Coding (DD+JOC). What makes this decision even more confusing is that Dolby’s own documentation seems to imply that the ideal future may actually be in a different delivery format – the one that Tidal is using, Dolby’s AC-4 IMS technology.

So why did Apple decide to use a less-than-cutting-edge delivery format that actually makes the music sound worse? Was using DD+JOC an arbitrary decision by Apple or a strategic move tied to its own immersive efforts around its own headphones?

Let’s take a couple of steps back to understand why anyone would care.

What does an audio engineer do?

For those of you who aren’t audio engineers, it’s important to note that audio engineers have wildly different philosophies on what “sounds good.” Some will debate for hours over the specific way to mix or record something the “right way,” while others take a more guttural approach.

Around the time that stereo started going mainstream, you may be familiar with what the Beatles did in separating instruments to different speakers: drums and bass on the left, guitar, horns, and strings on the right. While today that practice is quite rare, the point is that what “sounds good” in mixing is entirely subjective.

While there is lively debate about process and best practices, every engineer agrees that ear training is fundamental to every mix. An engineer must have the ability to listen critically, while confidently knowing what they mix will translate from a $500,000 7.1.4 speaker setup in the studio to a $50 mono Amazon Echo — and everything in between.

Engineers use expensive speaker systems to artfully refine the details of sound. But ultimately, they can’t forget that most people will probably listen on cheap headphones. Thus, engineers have all kinds of tricks to test their mix: listening in the car, a boombox in their kitchen, a Sonos speaker in the bathroom, a set of headphones they had in the early 1990s… whatever. So long as the engineer has enough context, the engineer can make important creative compromises during the mix to assure that a song can sound its best in most places.

In summary, engineers have to use their ears and find a sweet spot in the mix to fit as many listening situations as possible. Thus the Apple+Atmos issue presents an unnecessary obstacle in an already challenging creative process.

The 3rd Try

We are now on the third try of commercializing Spacial/Spatial/Immersive/Surround/3D music (read here for a more detailed history lesson).

- In the 1970s with quadraphonic sound on vinyl and tape.

- In the late-90s/early-2000s with 5.1 on DVD-Audio and SACD.

- Present-day with “Object oriented” formats like Sony’s 360 Reality Audio and Dolby Atmos on Blu-Ray, Tidal, Amazon, and Apple.

In most cases, the technology (and mostly the marketing of the technology) is far ahead of the listener. Each attempt compounds the inherent complexity of the technology itself with inevitable format wars around selling the technology.

When Quad died in the late 70s, the eventual result was that the film industry adopted the best elements of the technology. Four speakers in a square shape became four speakers in a diamond shape. That mutated to a star shape (5.1) which added a center channel dedicated to dialog and a subwoofer for so-called “Low Frequency Effects” (LFE). The LFE mostly came into existence because it was too expensive or cumbersome to have all of your speakers reproduce a full range of sound, specifically those super-low tones.

Upon the second attempt at “Surround Sound” in the late 90s, music co-opted the 5.1 film format. With that came heavy debate over what to use in those new center and LFE channels. Should you solo the vocal in the center channel? Should you cross over all low sounds under 80Hz into the sub?

The latest is an “Object oriented” approach, which attempts to ignore speaker configuration altogether. This approach puts the spatial processing more on the listening side of the process, allowing for limitless interactivity: seamless film language replacement, dialog attenuation for those hard of hearing, karaoke, Guitar Hero, VR exploration of a mix, whatever.

The rollout of these formats in all three generations seems to have similar results. No one is listening.

In the 70s, you were lucky to have one friend in the entire neighborhood with a “hi-fi” stereo, let alone a quadraphonic system.

In the 90s, there were boomboxes everywhere and even some modular hi-fi systems connected to TVs to compensate for tiny built-in speakers — but rarely a surround sound system. Even if someone had a surround-capable receiver, were all of the speakers connected? Are the rear speakers actually in the rear? Again, you were lucky to have one friend who bothered.

Today, it’s the same problem. Outside of professional friends who have spent many thousands (even hundreds of thousands) of dollars on Atmos mixing setups in their studio, I currently do not have a single friend with an actual 7.1.4 Dolby Atmos setup in their home. A small handful have soundbars that bounce the sound all over the room to emulate spatial sound.

This prompts the real question in all of this:

Does it even matter? My answer is no… and yes.

No

As I mentioned before, mixers are testing their mixes in all scenarios. No matter how you’re listening, if the song doesn’t make you feel something emotionally, who cares if it’s in mono, stereo, or surround? Plus, aren’t there nearly 200 million premium subscribers on Spotify? They’re not listening to spatial audio.

Yes

Virtual and Augmented reality is actually coming to, well, reality. With VR and AR comes sound to make you believe the visuals. The best way to ruin a VR or AR experience is to have shitty sound, completely removing you from a fully immersive, interactive experience. Give it a try. Shitty sound is especially shitty in VR.

Why

Why would anyone believe that AR+VR is really going to happen this time? Remember the 3D TV craze that came and went? Remember those futuristic “cyber” movies in the 90s? The Nintendo Power Glove? Massive technology companies have been investing many millions into “immersive” technology. These immersive attempts and all of the Spacial/Spatial/Immersive/Surround/3D music attempts died because the only people able to create and experience immersive anything were pretty damn rich.

In music, it was the top 0.1% of engineers mixing the top 0.1% of albums to be listened to by the top 0.1% wealthiest people in the world.

The bottom line is this: if the tech is too expensive or complicated, it will die. That’s what happened in the past. However, if it’s accessible and fun, the tech will thrive.

So what does this mean for spacial music?

Purpose

The yellow brick road to the seamless fruition of total immersion is happening. Making music in space not only opens up opportunities in VR, but more immediate and practical opportunities for licensing music for TV and Film. What do you think happens when an engineer delivers stems to TV and Film distributors? Generally, they mix the song in quad (or more speakers) and throw the dialog in the center channel. Over 200 million Netflix subscribers are listening, and Netflix requires immersive audio.

This new attempt at immersive music with Atmos, Apple, Tidal, and everything else is different than anytime before. In the era of a computer on every desk, a smartphone in every pocket, and inexpensive speakers in any Amazon box, the barrier to entry is pretty low. Real, working-class artists have been exploring and experimenting with these technologies for years now. It just finally got to the mainstream when Apple+Atmos announced their collaboration.

Plus, this go at immersion is fun and accessible: Oculus Quest 2 for $300. The new Apple AirPods for $180… and it will only get less expensive.

The Apple Problem

Now back to the Apple Problem. Apple’s use of DD+JOC and its own Spatial Renderer is strange, ultimately confusing listeners and discouraging musicians from bothering with immersive music in the first place.

Both the good and the bad of this situation is that the Immersive Audio we’re listening to on Apple Music will likely sound different in the future. In the future, it’s quite possible that the master files currently on Apple’s servers will get delivered and processed to the listener through different Apple Spatial Renderer and/or Dolby delivery formats. Maybe that could fix the problem or cause new ones. Even Giles Martin had to remix Sgt Pepper’s when Apple Music launched Atmos. Will he have to do it again?

Apple+Dolby’s financial and marketing resources are keeping the powers that be happy for now. But when that money and marketing go away, will our immersive music future go away too? I certainly hope not. My vote is for less remixing of old music to focus on the exciting creative opportunity with new music in immersive audio.

Are you with me? I’m sure that Apple and Dolby will figure this out.