Even though it was released nineteen years ago, OutKast’s “The Whole World” feels like the perfect soundtrack for these modern times.

Becoming an authoritative voice isn’t easy. With each individual Twitter account serving as an instrument in the infinite orchestra, sometimes the dissonance can outweigh the discourse. Yet hip-hop is full leaders, writers whose livelihood rests on being compelling orators. Especially for those who dare to explore complex themes societal equality, political status, and interpersonal connection. Doing so without credibility is a fool’s errand, and in a genre where artists continuously develop trust with their fanbase, a misstep can feel like a betrayal.

When OutKast first delivered “The Whole World” on November 27th, 2001, the Atlanta duo had long established themselves as reliable narrators. Those who observed the world as it was, who spoke frankly about issues without sugarcoating nor preaching. On the mic, Big Boi and Andre 3000 exuded wisdom as palpable as any OG figure, letting their vivid imaginations carry listeners through issues that might otherwise prove alienating.

As we’re currently in the midst witnessing, division runs rampant throughout western society. Tenuous relationships exist between entertainers and consumers, and in a predominantly black space like hip-hop, some conflicted listeners likely struggle to look beyond their prejudices. It’s all to ten heard that a rapper is “glorifying violence,” though many those same rappers are haunted by untreated post-traumatic stress disorder. And yet these critical listeners still return to the music, providing monetary support while holding disdain for the societal issues plaguing the black community. It’s a problem that has been prevalent since the rise rock and roll. Artists like Chuck Berry and Little Richard helped develop the culture and inspire iconic bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, all while forced to contend with the fallout a segregated era. The tenuous balance valuing entertainment while disregarding entirely the entertainer’s well being.

Brigitte Engl/Redferns/Getty s

It’s no wonder that OutKast opted to portray “The Whole World” as a circus, a concept reflected in the visuals and musicality alike. The imagery is evocative, leaving little to interpretation yet still effective. Andre, donned in the garb a tragic clown, serves as the main attraction, set upon by the gaze an entirely white audience. As the song opens, Three Stacks reflects on the painful relationship between fan and rap artist with frank simplicity. “Cause the whole world loves it when you don’t get down, and the whole world loves it when you make that sound,” he sings. “And the whole world loves it when you’re in the news, and the whole world loves it when you sing the blues.” Provided fans are able to retain a safe distance, an artist’s pain is all too easily received as pleasure; it’s the same reason why many are quick to praise a rapper’s darkest work, one created during a time personal crisis.

Leave it to the enigmatic genius to serve his satire with a smile. In his opening verse, Andre 3000 deftly dances his way through a variety topics. His vernacular, matched in scope by his imagination and all the more potent for it, make even his battle rap braggadocio sound refined. “Set a date sucker, in battle we can engage,” he spits, one with the bouncy lullaby. “I’ll slice you, wife you, marry you, divorce you, throw the Porsche at you is what I’m forced to do.” There’s something fascinating about Andre’s syntax, manipulating traditional word placement to suit his purpose — yet somehow sounding more eloquent as a result. Though his verse itself isn’t inherently political in nature, Three Stacks doesn’t need to say much to make a point. It’s a testament to his power as an authoritative narrator, where elements like a slightly weary cadence can sell his temperament better than any lyrical description.

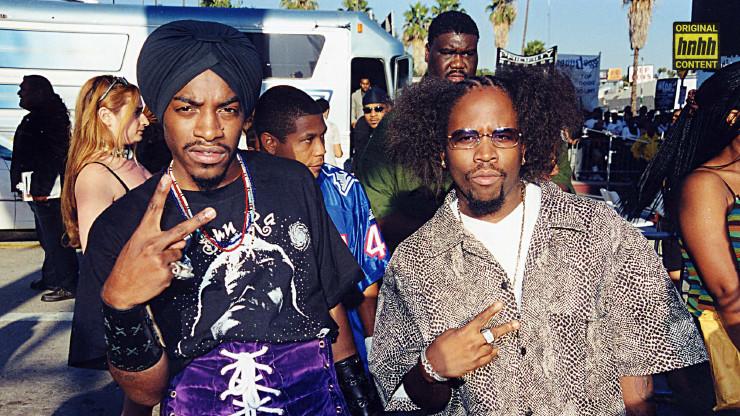

Jeffrey Mayer/Wire/Getty s

Given how far Killer Mike has come since first careening onto the scene with his debut album Monster, it’s hard to picture a time where he wasn’t passionately leading the charge in the fight for equal rights. Like Andre, Mike swerves the deeper commentary “The Whole World” is making, instead placing his lyrical prowess at the forefront. Interestingly enough, the complex dynamic between an artist and a politically-and-or-racially resentful fan would be a topic that the Mike today could easily discuss at length. Here, he’s simply part the performance, another act in the circus. Given that the rapper spent much “The Whole World’s” music video in front the American flag, it’s likely he had no qualms ruffling patriot feathers. How many current-day Run The Jewels fans would disagree with Mike’s political stances or challenge his philosophies on black excellence? While it may have taken him a while to evolve into the leader he is today, his involvement here indicates that he was always ahead the curve.

It’s only Big Boi who verses the song into overtly political territory, his opening bars painting a picture a world in turmoil. As the single was released only a few months after nine-eleven, where tensions with the Middle East were boiling, and George W. Bush was President the United States, it’s fair to say that Americans were overwhelmed with anxiety. “Wait, back to the enemy the state, is the Republicans or Democratic candidate?” wonders Big Boi, unable to make the distinction. It’s a familiar song and dance, one that has yet to slow nearly twenty years later. Politicians remain at odds. Hip-hop still stands as the dominant commercial musical genre, though many the same prejudices and judgments remain for those who craft it.

That’s not to say one must abide by everything a rapper claims in order to appreciate their music. But as “The Whole World” aims to point out, it’s disturbingly easy to pass judgment from the sidelines and dehumanize an artist. Though Big Boi advises he and his groupmate look inward for inspiration, that chorus dissonant voices can feel overwhelming. So next time you think resenting Andre for his absence, instead choose empathy and aim to understand why he took a step back. You may love it when he makes those sounds, but is it really worth it if all he’s singing is the blues?